Are landlords profiting by keeping units vacant?

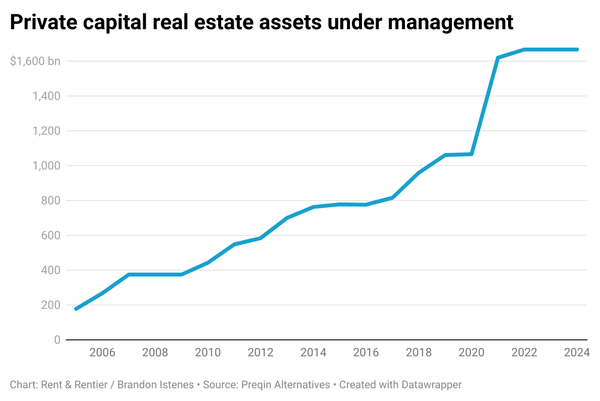

Many people, myself included, think that finance has some important role in why the rent is so damn high. There is a growing "housing financialization" literature about this. The idea is that banks, investors, and other financial actors are driving up home and rent prices. This was a key part of the 2000s housing bubble. It's clearly an important theme, and it deserves serious attention.

But this post is about a housing financialization idea you hear often, but rarely see in the research. The idea is that landlords make more money by keeping units empty. Miguel Robles-Duran expressed this in a fairly erudite way in a panel on housing recently. The idea is that a building owner can raise rents and tolerate high vacancies in order to overvalue the building and leverage it up into additional loans, net increasing their profits. I'll explain how that would work in the next section. But basically, it's theoretically plausible, a good hypothesis. So let's consider it.

Can landlords make more money by keeping units empty?

Andrew Burleson of Strong Towns wrote a great explanation of why rents don't go down in vacant buildings. I encourage you to go read it and come back here. But the basic idea is this. An owner finds a creditor to help buy a building. They agree about how much the units should rent for. A few years later, it turns out they were wrong, and there's still 50% of the units vacant (~10% is the usual assumption during underwriting). You would think that the reasonable thing to do would be to reduce rents. But if they do that, they may have to foreclose. Neither party wants that. So they "extend and pretend" with the assumption that eventually market rents will catch up to what they're asking. The way the math works out, this can go on for many years and still be preferable to foreclosure.

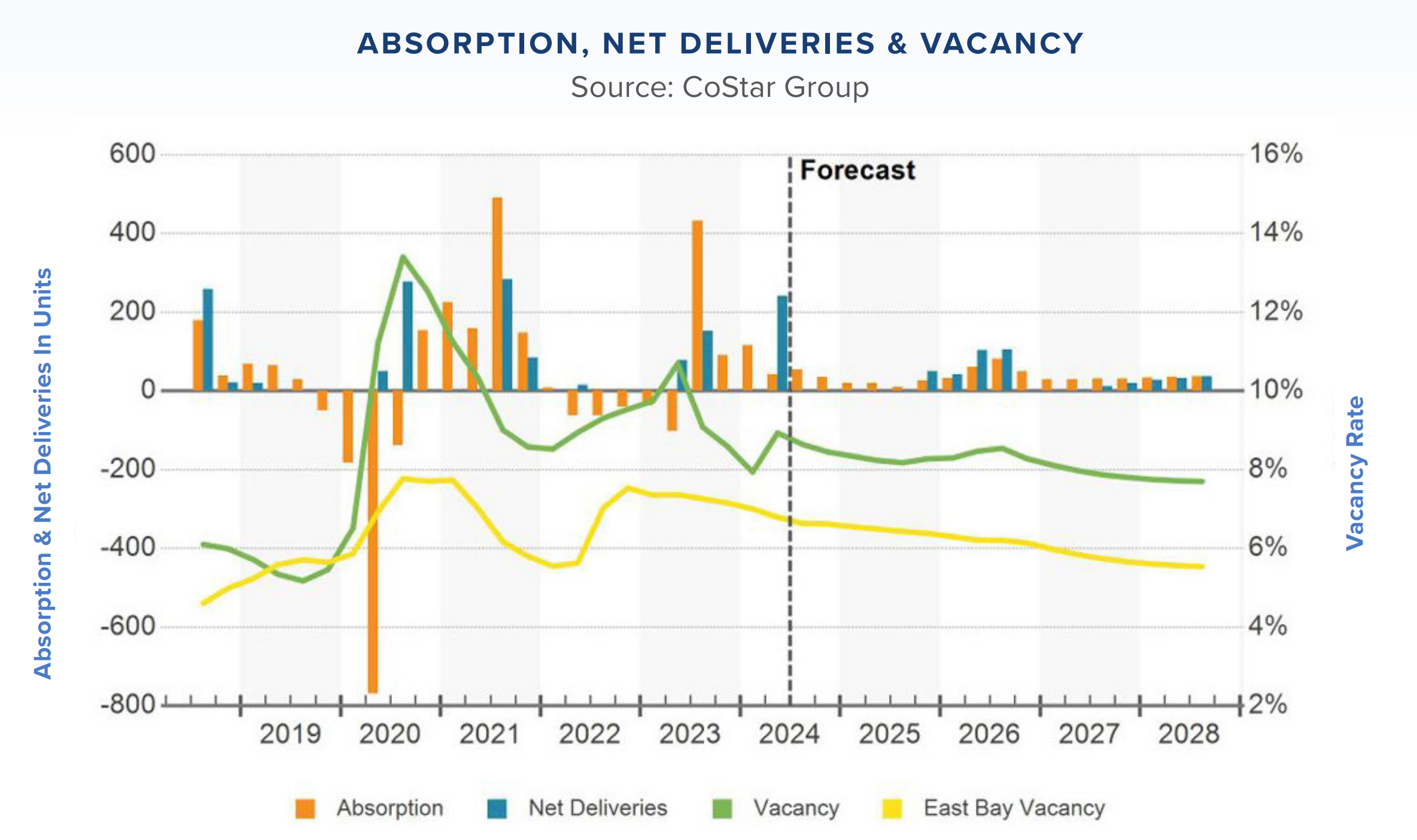

There is no doubt that this happens when prices fall. When the pandemic hit Berkeley, CA, all the students left. A huge source of local housing demand suddenly dried up. The vacancy rate briefly spiked, and has remained 1.5-2x the historical norm in the subsequent years.

Many units just sat empty. As late as 2023, upwards of 30% of rental units had listings that stayed up for more than 180 days (per Rentcast data). In 2024-2025, it's less than 5%. This was similar for both single-family homes and apartments. Some of these long-term vacancies were probably just because landlords figured the market would recover quickly and didn't want to lock themselves into a low rent for a year. But many were likely tied up in loans and facing a foreclosure risk.

It's hard to see these kinds of patterns in overall price data. When we look at the local indices, we see that rents did dip during the pandemic, especially close to campus.

Once the Covid vaccine rolled out, rents bounced back—even though vacancies stayed high.

I was on vacation with some friends from Oakland recently (hence the delay between posts, sorry). They were telling me that after the pandemic, rental listings in many buildings in Berkeley simply did not go down in price, despite being listed for years. But they were seeing move-in discounts. As Burleson points out, this is a way that owners can produce some income flow from an overpriced unit without facing foreclosure. In the last couple years, some of the most overpriced buildings finally dropped the rents. Either they took the loss, or else lowered rents just enough to fill the units and stay solvent.

It's anecdotal evidence, but it makes sense with the mechanics of real estate finance. I'd love to see a building-level analysis of how much this actually happened across Berkeley.

Ok, but is this a money-making strategy?

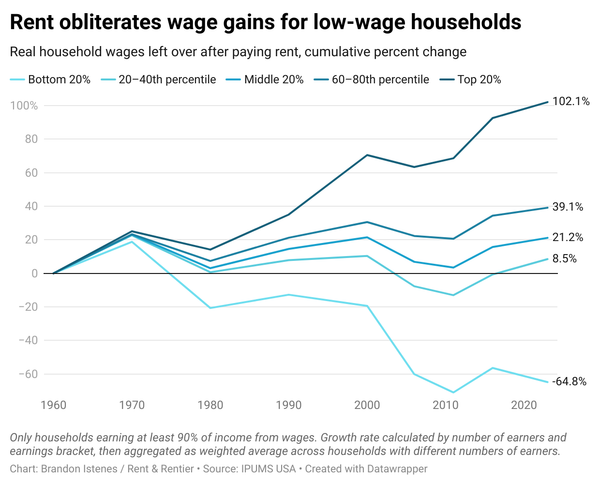

So there's no real debate that this helps explain why rents don’t go down. At least, not in nominal terms—rents relative to wages sometimes do, but that’s a topic for another post. But is this also a reason rents go up? How would that work?

Let's try Andrew Burleson's example in reverse. I'm going to buy a building and raise rents to inflate its value, then use that inflated value to get a loan. Let's say Burleson sold his building to me for $14M, based on $700k annual rental income and a 5% cap rate. I get an $11.2M loan to finance the purchase. Then I hike the rents. If nobody moves out, the building now brings in $1M a year.

Of course, that’s what Burleson tried. But I’m being wiley. I expect vacancies to spike. Let’s say I lose half my tenants and the income drops to $500k. Still, on paper, the building looks like it’s worth $20M. That gives me $8.8M in equity. I can use that to buy another building, cross-collateralized. If the second one cash flows well, I might make up the $200k lost from the first.

Just one problem: the building is only worth $20M if it brings in $1M per year—or if a creditor thinks it will. In Burleson’s case, both buyer and lender believed in that future rent. The deal happened before the building was up and running. They were guessing.

That’s not true in my case. If I approach a creditor and say "Here's my $20M building," they're not just going to fork over some cash. They're going to check the books. They'll see I'm pulling in $500k annual rental income. They will tell me that no, they are not going to collateralize a loan with my $10M building.

So it doesn't seem likely that this could actually work. Then again, in the 2000s people were getting rich off making bad loans that ultimately could not be paid back, so who knows what mysteries the financial system has in store.

Well, is it happening?

If it's happening—and again I don't think it's likely—it's certainly not a meaningful driver of increasing rents. There are a few pieces of data that make that clear.

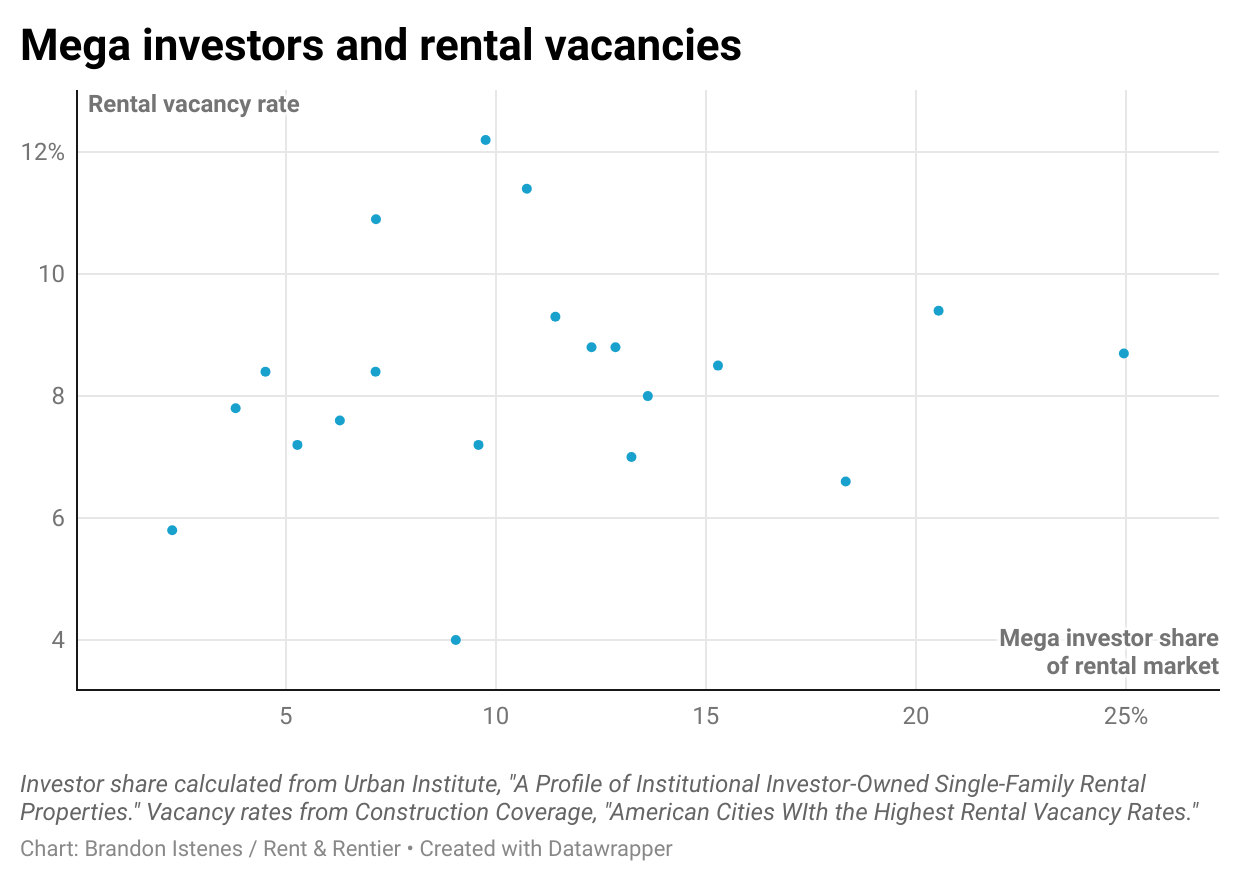

First, if anyone is able to pull off this kind of strategy, it's probably large institutional owners. But small landlords (1-10 properties) make up maybe 90% of investor purchases. Large institutions own only a small share of US rental properties. Even in the metros with the most institutional ownership, it tops out around 13%. In most places—including the most expensive markets—it’s below 2%. That’s nowhere near the market power needed for this strategy to drive prices. And there’s no clear link between high vacancy rates and institutional ownership.

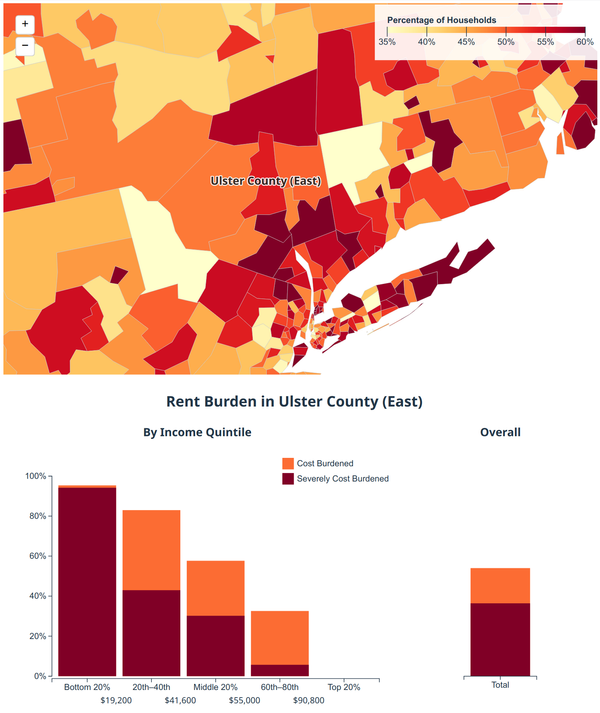

Vacancies don’t match the theory geographically either. The states with the highest rental vacancy rates are Arkansas, Indiana, South Carolina, Alabama, and Texas. These are not states which are famous for high rents. On the other hand, New York City is in the bottom 20% of metro vacancy rates. My town, Kingston, NY, has such a low vacancy rate that it triggered a housing emergency under New York's Emergency Tenant Protection Act. After the pandemic, Kingston had the fastest rent spike in the country. If landlords are pursuing a profit-through-vacancy strategy, you have to wonder why it isn't affecting vacancy rates.

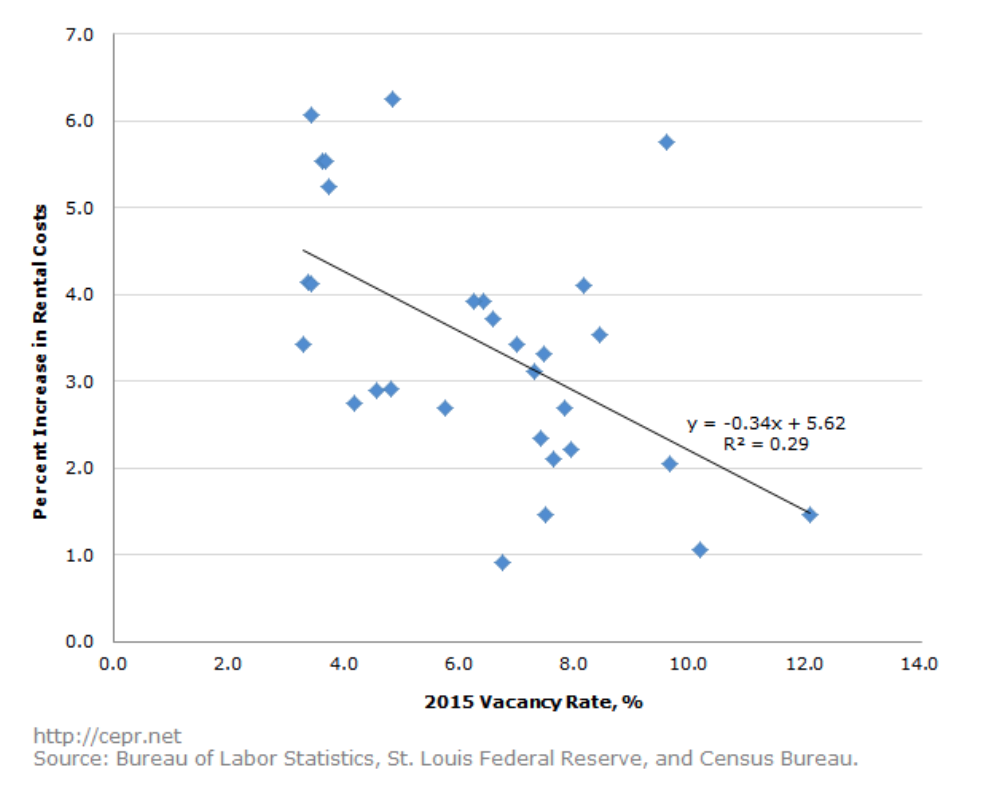

There’s also a strong pattern across cities: higher rents usually mean lower vacancies. As we saw in Berkeley, the behavior of prices in a place over time is complex and path-dependent. But look across metros at a single point in time, and the relationship is obvious. Here's a chart from CEPR for 2015:

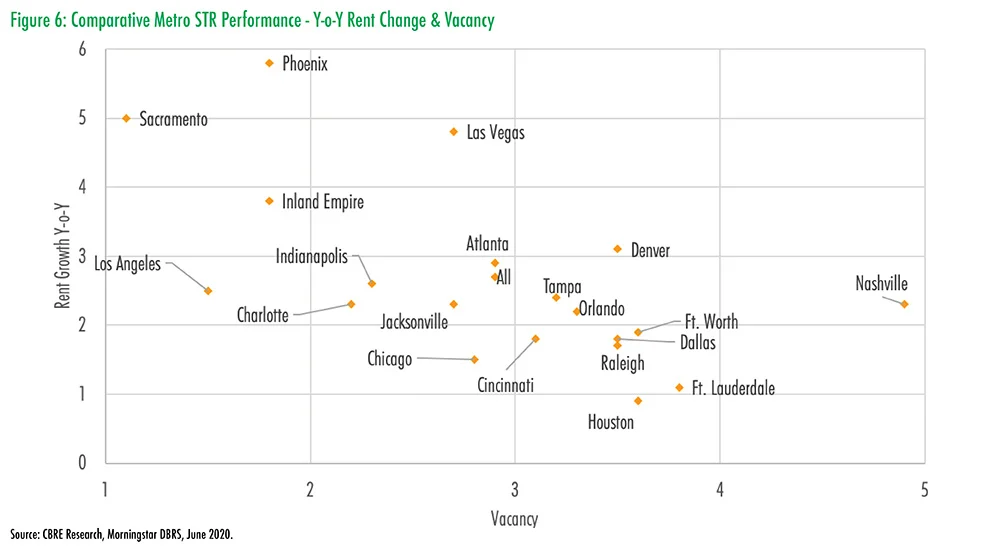

Both the lefty think tank CEPR and the definitely-not-lefty real estate investment firm CBRE agree. Here's a similar chart from CBRE for single-family rentals in 2020:

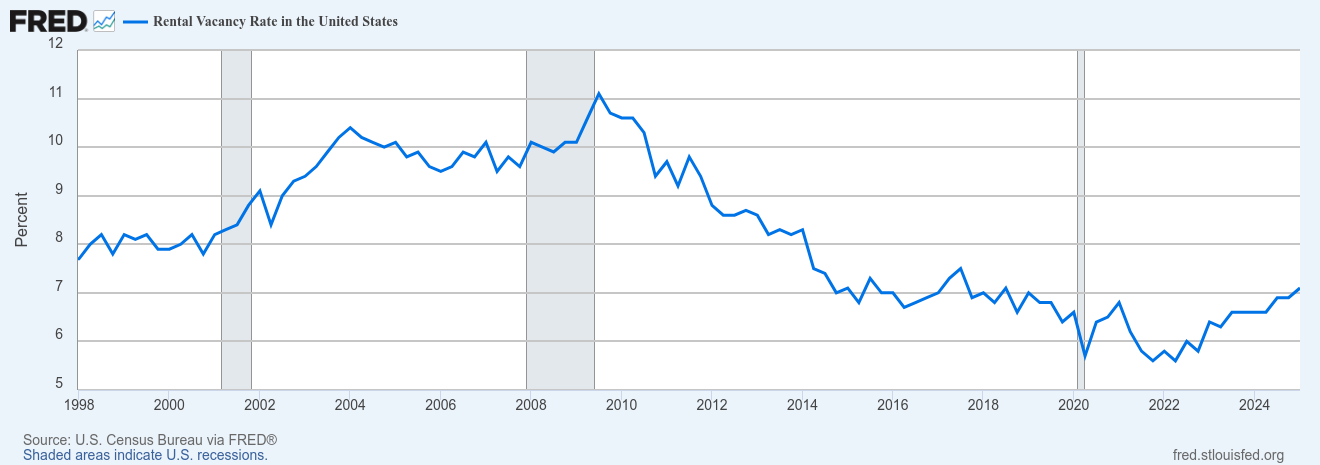

This also fits the national story. Vacancies were at a historic low point when the rent spiked in 2021-2022. In the 2000s, price increases were driven by loose finance. In the 2020s they were driven by internal migration. People wanted to move and there just wasn't anywhere empty to move into. Fortunately, the vacancies line is ticking up. In the abscence of a new financial bubble, rent growth is moderating.

It's not looking good for the "profit from vacancy" hypothesis. But two important caveats are warranted.

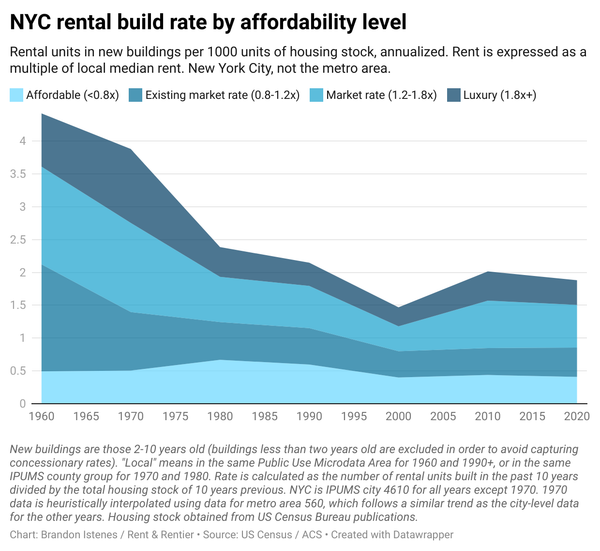

Luxury vacancies probably do raise rents, but not as a profit strategy

First, luxury units have much higher vacancy rates than other rentals. In Q4 2024, the national multifamily vacancy rate was 8%. For luxury units, it was 11.4%. These very reasonably could contribute to rising rent prices. They contribute to the distribution of listed prices that other landlords see when they are figuring out how much to list for. They legitimate higher market prices by being on the high end of the market. They "anchor" price expectations, raising the price at which both landlords and tenants think they're making a good deal.

How important is this in the overall story of rising rents? Probably not very. For one, places like Kingston, where rents have risen very fast, simply don't have "4- and 5-star" units. And then there's the fact that the places where rents have risen the fastest, both in the 2000s boom and the 2015-present period, are the low-income areas in expensive metros. Not likely targets for five-star developments.

These units weren’t priced high to leave them vacant and profit. They are vacant because developers overestimated high-end demand. They're waiting out the market to avoid foreclosure—the Burleson story.

There is a tradeoff between vacancy and high rents

I suspect not many of you reading this believe that landlords are "price takers" in the neoclassical sense (that they just charge whatever the invisible hand of the market compels them to). You're right. A recent paper from Gonçalo Costa called Dynamic Monopoly in the Rental Market demonstrates this rigorously.

Costa shows that landlords, like monopolies, face downward-sloping demand. That is, they can raise prices and accept some vacancies. So there is a range of rents that could be profit-maximizing—$1000 times 90% occupancy is the same as $1200 times 75% occupancy. They can't charge any rent they like, but they have some options. This happens not because of market concentration (as in classical monopoly), and not because of collusion. It's just the ordinary "frictions" of the rental market.

This kind of market power absolutely matters for aggregate rent dynamics. But I don’t think it explains the big rent surges—like in the 1970s or now. This is because I don't believe that landlords magically lost this discretionary power during the stable rent periods, such as the US 1960s, 1990s, European 15th-19th centuries, Germany 1960-2010, or Tokyo 1990-2020. It's part of the story, but not the key driver.

What about rent controlled units?

There’s one last version of the “profit from vacancy” idea. Maybe Robles-Duran was talking about rent-controlled units in NYC. According to the landlord group CHIP, there are at least 26,000 units that need enough repairs that they could only be operated at a loss. So they sit vacant. It is plausible that these buildings are used as collateral for other loans—loans used to buy income-producing properties. This would be a case of leaving units vacant to increase profits through leverage. Profits would be increased from a negative number (if the landlords are to be believed—though frankly I don't know why else they wouldn't fix and operate those units) to a positive number.

This is sort of a special case. It's quite restricted to NYC. And it's probably not the result of a nefarious landlord plot (not that they aren't nefarious). They just aren't trying to lose money as a business plan. Maybe I'm missing something—if you can explain why one of these landlords would opt not to repair and rent a rent-controlled unit when it would be profitable to do so, please shoot me an email.

Note: After I wrote this, I found an earlier video from Robles-Duran in which the two things he cites are the 50% vacancy rate of Billionaire's Row in NYC and rent controlled vacancies. So I think I've done this idea justice here. Early in the video he says he is laying out a sketch of his thoughts at that point, and that he welcomes feedback, so I hope he takes this criticism as comradely.

Wrapping up

One goal of this newsletter is to engage with the connection between finance and housing. I think it should be taken seriously. But taking it seriously also means trying to evaluate claims empirically.

I'm still early in this research, but my feeling is that many of these finance connections are indeed important. There's almost certainly a relationship between rental de-risking and growing investor demand. Josh Ryan-Collins has a very good book on the relationship of mortgage credit to long-run house prices. Finance obviously was front and center in the 2000s bubble. And prior to modern banking, housing costs were remarkably stable for the centuries on record. So I'm going to keep digging. Thanks for reading. And if you’ve got stories about the weirdly vacant buildings in your neck of the woods, please send them my way.