How much does luxury building matter?

The results of this one were a big surprise to me. The question I asked is, are rents high because the new housing that's being built is too expensive? There's a lot of attention on how expensive market-rate housing is and how much luxury vs affordable housing is being built. And since construction is so much more expensive than it used to be, my intuition was that housing built today is probably much more unaffordable than the new housing of the 1960s.

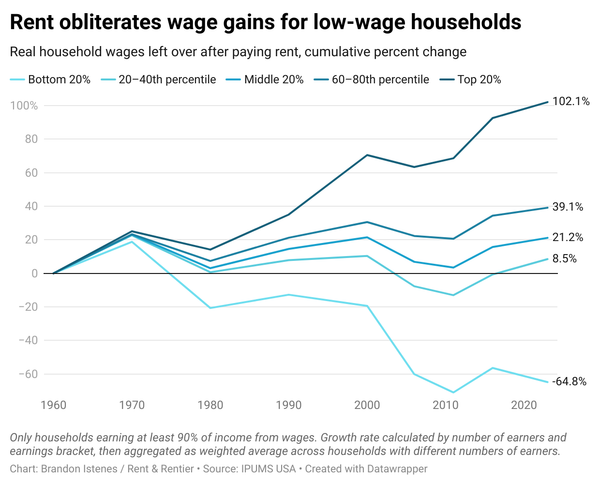

As discussed previously, housing affordability has been in decline since 1960, with the periods of steepest decline being the 1970s and the 2000s.

In fact, it's likely that around 1960 was the high-water mark for housing affordability in the US. Here is how median rent compared to median wages going back to 1940. I'm showing the comparison both to the median wage across all persons and the median wage just for renters. As you can see, renters have increasingly tended to be poorer over time.

So the question is: how much of this decline in affordability is due to developers increasingly preferring to build luxury units?

Have we been building more expensive new units than we used to? In a shallow sense, definitely, yes—inflation-adjusted rents for units built in the last ten years (which I'm going to refer to as "new units") have more or less doubled since 1960.

Note that I'm excluding rents in units less than 2 years old in order to avoid capturing concessionary rents (move-in discount etc.), which are very common in new buildings.

But that doesn't necessarily indicate a developer preference for building fancy buildings. For one, some significant portion of the rise can be chalked up to rising construction costs. Here is an index of construction costs over time, from Shiller.

This is a sort of mechanical part of the story of why housing has gotten more expensive. Building homes is expensive, and the rent charged has to cover the (debt service for the) cost. This is what we would call a "fundamental" determinant of rent prices. Clearly, though, the above two graphs are not the same, so there's a lot more to the story.

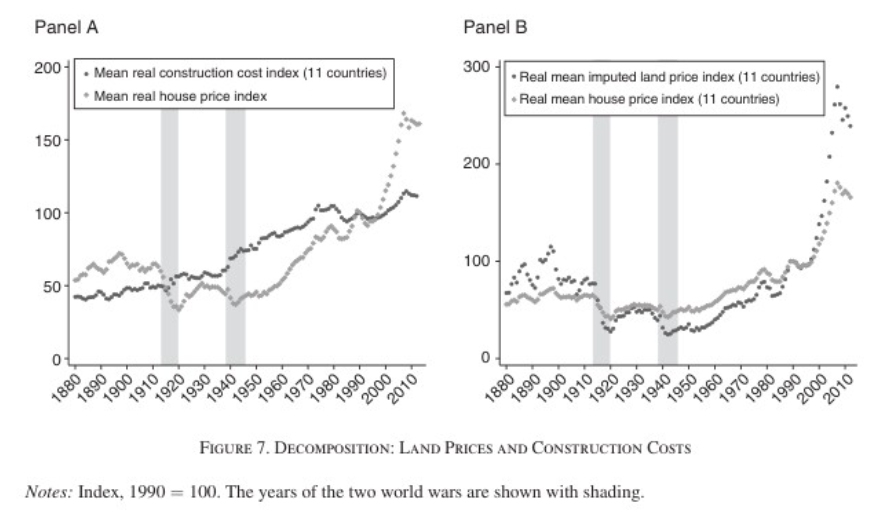

There are other cost drivers associated with new development, such as land costs, taxes and permitting fees. These have all also gone up—land costs and permitting fees have gone up in real terms (i.e. on an inflation-adjusted basis; I don't know about taxes). Here is a terrific chart from a terrific paper—Knoll et al. 2017—in which house prices are compared with a construction cost index and a land price index.

For the purposes of this post, we'll consider all these costs boring. Of course they're all very interesting in their own right, and have interesting things to say about why things are expensive, but right now we're focused on developer discretion. They didn't used to build this much luxury housing, did they?

First let's look at the incomes of people that live in new housing. Who are we building housing for?

While the top-end of the renter income distribution occupying new housing has been increasing since the 1980s, it is only just back to its 1960 level. So it doesn't really look like the new housing we're building is just for rich people any more than it was in the decade leading up to 1960, when housing affordability peaked. In fact, one of the most dramatic periods of affordability decline—the years leading up to 1980—is when the income distribution of new rental buildings was most equitable.

The results across all households in the US, including owner-occupied, are similar, but with a bit less variation over time.

But housing has been getting much more expensive. Are people paying a larger share of their incomes to live in new housing? No, it turns out. While cost burden has increased overall, it doesn't seem like there is or ever has been a "cost-burden premium" that people are willing to pay to live in a new building.

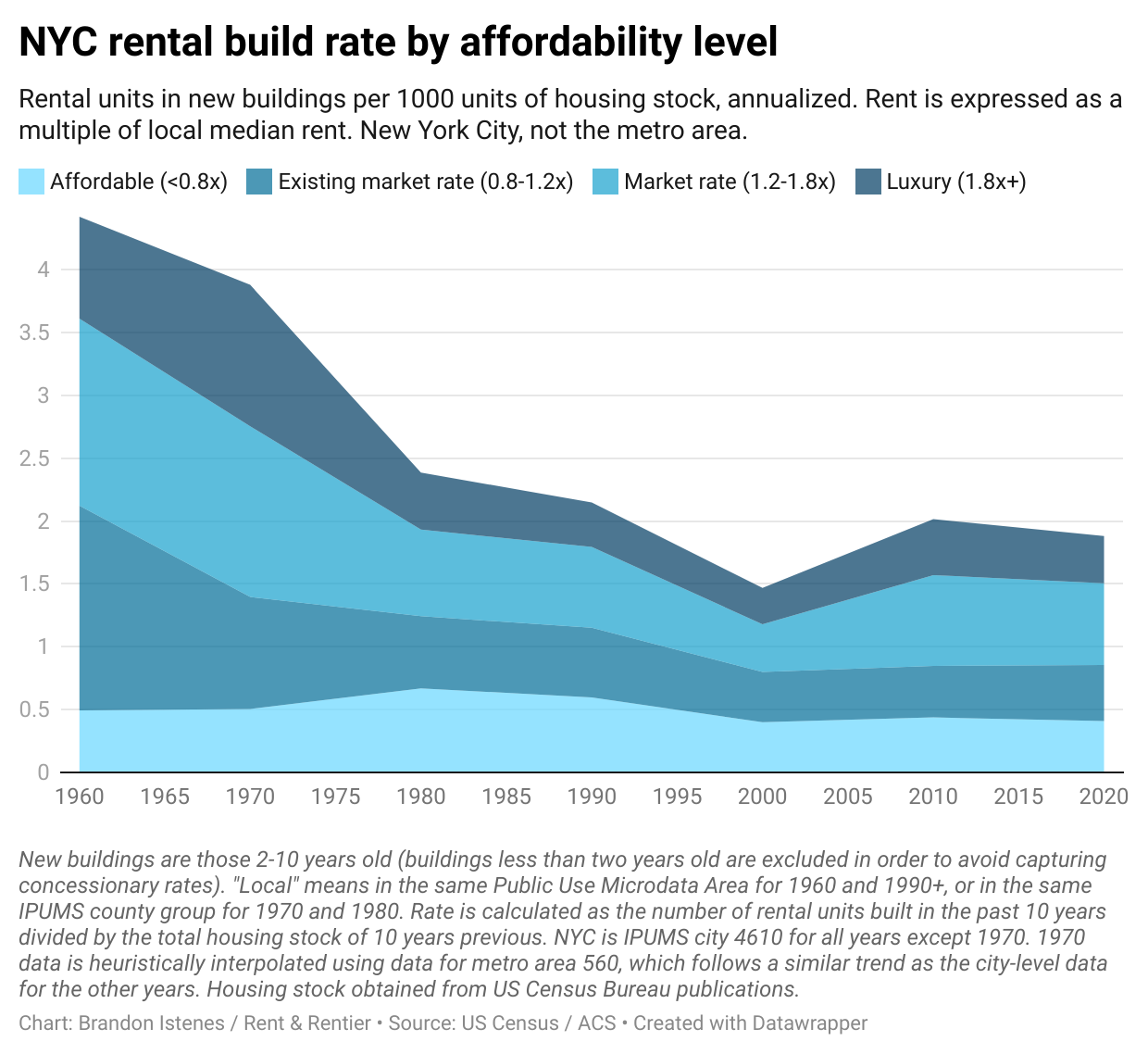

Let's look at this another way. Let's look at how the rents of newly built units compare to rents being charged in the existing market. I've loosely categorized the buildings by rent level, calling a unit "luxury" if it charges more than 1.8 times the median local rent, "market rate" if it charges 1.2-1.8 times the median local rent, and so on.

Note that the years in the chart are the end of the decade the building was built. So "1960" means buildings built in the 1950s, and so on.

So how much higher than the local median rent are new buildings charging?

This was really surprising to me. The luxury share of new development was higher in the 1950s, and substantially higher in the 1960s, than it is now. The luxury share of new development has increased a little bit since its low point in the 1980s, but not by all that much.

Note that this graph looks pretty similar across different regions, for different definitions of "local", and for different categories of housing (e.g. whole market vs commercial (5 units+) only).

What makes this so remarkable is that the period with the most luxury development was also the period of greatest housing affordability for the working class, possibly in US history.

That is not the result I expected from the data. I thought that between rising construction costs and rising developer concentration, we would see a clear trend toward more luxury development since 1960. And then I would have to explain that while filtering is real and important, the upper end of new builds seems to lead market prices. But I asked the data whether that's true, and it told me I was wrong. Upper-market development does not, at least over a long time horizon and wide geography, seem to drive market rents.

Not so fast, pal

There are a few caveats to interpreting this. First, we should look not just at the distribution of rents in new builds, but also the rate at which we were building.

We can combine our two graphs above to look at how many new units were being built (per 1000 stock) at each rent level.

Note that I choose to combine using the "rental build rate" rather than the overall build rate, because the rent distribution only makes sense for rental units. But it is worth noting that the affordability of the 1960s probably had more to do with the overall build rate than the rental build rate, as new homeowners also would have freed up rental units.

The rate at which relatively affordable rental housing (<1.2x local median rent) was being built in the 1950s was about equal to the rate at which rental housing of any sort was built in the 2010s. And this doesn't even touch the build rate of the 1970s.

So on one hand, it's possible that the high overall build rate was a driver of overall affordability prior to 1980. On the other hand, it's possible that the rate at which low-end units were being built is what's actually important, and that rate too was much higher back then.

The story is only slightly different in the most expensive US markets. Here is the breakdown for NYC.

Here we see that the 1950s had the highest rate of building new rental units in NYC out of any decade I have data for. The share of luxury housing was 18% in the 1950s, 29% in the 1960s, and about 18-22% in decades thereafter. The share of affordable housing was tiny—about 12% of all new housing—until every other kind of housing collapsed. Since the 1970s affordable housing has been 20-30% of all new housing in NYC.

Note that the historical arc of rent prices in NYC looks similar to the story nationally, but with much worse affordability in 1940. For 1960 onwards, the years for which I have rent burden data, the share of rent burdened New Yorkers looks similar.

A note about choice of build rate

It looks in the charts above that the rental build rate reached its maximum in the 1970s, but that affordability was substantially worse in 1980 than in 1970. This would suggest a problem with the supply story. But if you look at the overall build rate, you see it decline dramatically from 34 units per 1000 per year in the 1950s and 1960s to 25 units per 1000 per year in the 1970s. It makes sense that the overall build rate would be more relevant for overall affordability, since many new owner-occupied units will have freed up rental units for someone else.

What do you make of it?

Of course this doesn't really prove anything. But it does help us get a clearer sense of what affordability conditions in the past were like.

First, there are two competing stories that are both more or less compatible with these findings:

- Housing is expensive because we build way less than we used to

- Housing is expensive because we build way less affordable housing than we used to

However, I think the distinction might be less important than it seems. In practical terms, the major policy levers we use to encourage more affordable development, such as LIHTC and inclusionary zoning, were introduced in the 1970s and 1980s. This was also the era when modern zoning regulations came about, which is likely what resulted in the massive construction slowdown of the 80s and 90s. Comparing the share of below-market-rate development in the 1950s to that in the 2010s, it does not look like policies encouraging affordable development have been successful in any sense. I wouldn't go so far as to construe this data as evidence against inclusionary zoning, but it does not seem supportive of it.

Despite 50 years of policy to encourage more affordable development, we build less affordable housing than we did in the 1950s.

Despite building more upper-tier housing in the 1950s than any time subsequently, working-class housing affordability peaked around 1960. Again, while this doesn't prove anything, this data is not supportive of the idea that building luxury housing drives up rents generally.

This data would, on the other hand, seem to be explained well by filtering.

Evidence for filtering

There are two things people mean when they talk about filtering:

- Building depreciation—units get cheaper as they age

- Migration chains—people moving into fancier units, freeing up more affordable units for others

Building depreciation is known to happen slowly, maybe 0.5% per year. But chains of move-outs and move-ins accelerate this process dramatically.

The most important evidence about filtering is without a doubt Evan Mast's 2023 paper in the Journal of Urban Economics (see the 2019 working paper if you don't have access to JUE). He tracks actual chains of move-ins and move-outs of actual households to demonstrate that housing submarkets are highly permeable. Market-rate construction frees up affordable housing. Even if you don't like the assumptions involved in the simulation, the descriptive statistics speak for themselves.

Migration chains happen fairly quickly, with an average of three months between each move-out and the next family's move-in. The result is that building 100 new market-rate units ultimately leads to about 40 new vacancies in below-median income neighborhoods.

Maybe you think, as I do, that landlords (especially savvy ones) take advantage of price anchoring and gentrification (/"amenities") effects to raise rents when new luxury housing goes in. I think those effects are real. But they would have to be extremely powerful to counterbalance the filtering effect demonstrated by Mast.

This suggests that even the upper-tier housing built in the 1950s and 1960s ultimately resulted in increased housing affordability. That housing affordability in the 60s was not because of the affordable housing and despite the market-rate housing, but rather because a lot of housing in general was being built.

There is evidence from Zuk and Chapple that subsidized units do more than market-rate units to slow displacement and speed filtering. This makes sense. But we so far have not been able to find a policy framework that allows us to build lots of affordable housing and less market-rate housing. The history of the US is one in which we were building lots of affordable housing and lots of market-rate housing, and then very little of either.

As a side note—migration-based filtering happens both "down" and "up." When there aren't enough nice homes for upper-middle-income people to move into, they will move into houses that would otherwise have been affordable and renovate them. This is called "filtering up." Here in the Hudson Valley there is a whole HGTV show about this. The show pissed off a lot of people, including many who at the same time oppose building the market-rate housing that would prevent this from happening.

The socialist perspective

As I suggested earlier in the post, these findings were a big surprise for me. I expected this post to go something like "we used to build much more affordable housing, so despite the fact that filtering is a real thing, the increasing share of luxury housing is necessarily part of the affordability crisis."

I am sharing this data as a matter of integrity, and because I am ultimately more interested in advancing universal access to affordable and ecologically sustainable housing than any particular set of ideas about how to achieve that.

Nevertheless it's important to think about how these results fit into that perspective.

We might consider three kinds of loosely socialist goals* in housing (you may have one, two, or all three!)

- Social-democratic: the universal right to affordable and ecologically sustainable housing

- Pikettian/Georgist: eliminating the extraction of economic rents

- Communist: eliminating the profit motive in the development and management of housing**

You will notice that none of those are "ensuring that new buildings have low AMI units." The social-democratic commitment requires that affordable housing be created. But none of these commitments demand, for example, upholding inclusionary zoning and AMI restriction as effective policy tools. One can maintain socialist commitments while accepting the overwhelming evidence that filtering is effective. Just as one can oppose the capitalist pharmaceutical industry, for whom the profit motive is rife with perverse incentives, while accepting the overwhelming evidence that vaccines are safe and effective. Supporting vaccines does not make you a shill for big pharma, even if it is in line with their business interests. And if it makes you feel better, you should know that hedge funds do not want more supply.

This provides a very useful insight about policy tradeoffs: from the socialist perspective, the priority is bringing the management of housing into the hands of the public, cooperatives, and other non-profit actors, as well as creating capacity for housing to be built on not-for-profit basis. Public rights and stakes are more important than AMI requirements. And of course, the establishment of public development institutions should remain a top priority at the state and local levels.

*not an exhaustive list**honorary mention for what I might call "Jacobsian": the empowerment of local working-class people to build and renovate, to participate in shaping the communities they live in.