How to fight big financial landlords

The role of big finance in housing has been getting a lot of attention lately. TikTokers made a big scare and convinced a lot of people that 40% of single-family homes are owned by private equity companies, which is not even close to being true. This turned out to be based on a prediction that private equity could own 40% of SFH, which was a prediction made in 2022 based on explosive growth in 2021 that has since dried up.

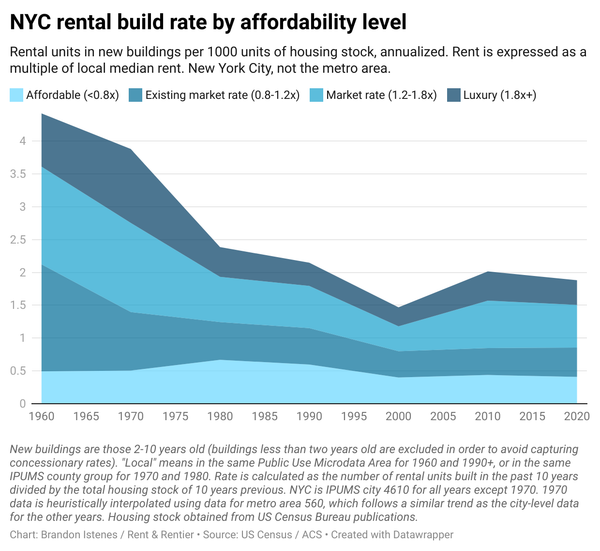

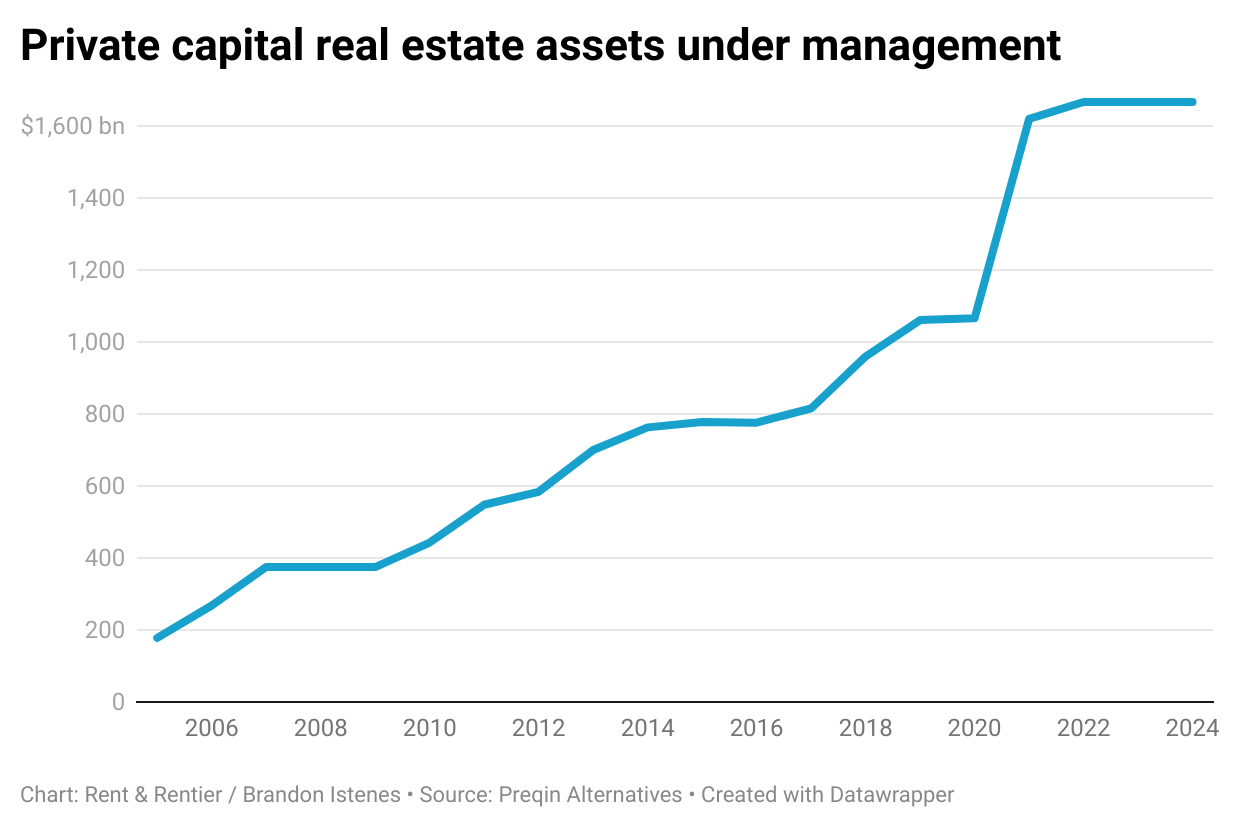

Here's a chart that shows real estate assets under management (AUM) in private capital (so private equity, hedge funds, non-public REITs, etc.).

It was slow and steady increase until 2021, explosive growth in 2020-2021, then a leveling out after that. Right now private equity is actually net divesting slightly from single-family rentals—nothing major, but 40% by 2030 is absolutely not in the cards, unless there's another massive shock that triggers another investor buying frenzy.

A caveat to the graph above—probably only about 30% of AUM is residential. Also the numbers reported above are rough. So to get apartments + SFH, divide those numbers by three and you'll be in the right ballpark.

Big financial landlords are a problem

That said, it is very reasonable to be concerned about financial institutions owning homes. There's a great new piece of research from Toronto, August & St-Hilaire 2025, that explains why. The key is that large institutions are able to be very sophisticated in how they set rents. As we learned in the last post, there is strong evidence that landlords have some flexibility in where they set rents, even if they are specifically aiming to maximize profits. This new paper shows that large institutions can and do raise rents much faster than other types of landlords.

Because they have lots of properties in their portfolios, they can do clever things like "using 'test suites' to see just how high rents could be raised" (p.5). They run little experiments where they raise rents a bit in some units, a lot in some others, and see what's the maximum the market can handle.

In the paper, they find that specifically financial-sector landlords are doing this kind of thing, and raising rents faster than anyone else. This is especially true for lower-end buildings. Ordinary corporate landlords were not raising rents nearly as fast, except for in luxury buildings.

Let's put a few numbers to it. For listings in class C buildings,* individual landlords were pricing 21% higher than average neighborhood rent, and corporate owners and corporate property managers around 29% higher. Financial landlords were asking an average of 40% over neighborhood rent. Class B buildings exhibit a similar pattern, and for class D (low-end) the difference is much more dramatic—13% for individual landlords vs 43% for financial landlords.

*Class A is modern and fancy, Class B is recent and decent, Class C is older and affordable, D is for distressed.If you want to see the full breakdown of the numbers, consult the paper. The "Qualitative analysis" section is very accessible and full of insights about how financial firms think about real estate.

Firms using YieldStar, the price-fixing software from RealPage, also get a mention. Financial firms coordinate price strategy across their portfolio, so while they have the sophistication to raise rents as fast as the market will bear, they generally don't have price-fixing power. YieldStar has caught a lot of well-deserved flak for being a price fixing scheme, but that only really works where their clients have significant market share (like Seattle, where the 10 property managers that oversee 70% of the apartment stock all use it). This paper shows that in places like Toronto, where YieldStar is not much used, it can still guide landlords into pricing strategies that mimic the aggression of the financial firms.

So that's bad.

How not to fight big financial landlords

A bill has been proposed in the US Senate which aims to fight back against private equity ownership of single-family homes. It demands that large financial companies, such as hedge funds, sell off their single-family homes to owner-occupiers over the next 10 years.

For all the reasons covered above, reducing financial institutions' share of housing is an excellent goal. Unfortunately, what the bill demands is in effect the eviction of 700,000 renters, disproportionately poor, single mothers, and renters of color.

There is zero chance that this bill becomes law. This is for three reasons: it is a bad bill with a bad idea, the US government is currently run by outright fascists, and elected officials broadly are not very concerned about the role of big finance in housing. But we can usefully contrast it to what might be good solutions to the financial landlords problem.

Credit where credit is due, I found out about this bill from Kevin Erdmann's excoriating piece on it, and his analysis has certainly informed this one. Erdmann is a housing economist with very different ideological commitments than my own, but I really respect his work developing a coherent theory of the housing crisis that agrees with empirical reality. That is, ultimately, what this newsletter is also trying to do.

What the bill would do

As proposed, the bill would use a tax to push large institutional owners of single-family homes to sell them to people that don't own any other homes. The thing about homes owned by institutional owners is that, like most homes owned by landlords, they have people living in them. If they sell to someone else who wants to live in that home, the person currently living there cannot keep living there. According to the 1-pager, this would impact about 700,000 homes. They will have to move out so that the new owner can move in.

Erdmann said it, and I just can't see any way he could be wrong about it. There is no way to weasel out of this conclusion.

"What if the renters buy the houses they currently live in?" A large segment of renters, and especially the poorest renters, are renters at least in part because they cannot obtain a mortgage to buy a home. They can't afford it. They will not suddenly be able to afford it.

"What if the sell-off causes home prices to drop enough so they can afford it?" This simply will not happen. Home prices will drop a little bit, but not enough to enable more than the top, maybe, 10% of renters to become homeowners.

Let's walk through what would happen in Atlanta, the US city with the highest institutional ownership of single-family homes, about 13% of the stock. More homes would go on the market as institutional investors look to offload their SFH. Supply goes up. At the same time, the segment of demand which institutional investors constitute evaporates. Demand goes down. So prices go down, right? Well, as we learned in the last post, landlords have to decide what kind of losses to accept. If house prices go down too much, institutional investors will simply eat the $5000/year tax and wait for the market to recover a bit. Since they have deep pockets, their ability to wait places a floor on the ability of house prices to fall.

This is not terribly different from the behavior of normal homeowners or individual landlords during a downturn. One of the reasons that house prices in general do not go down is that homeowners will simply wait out a bad market, delaying moving or selling until their beloved home is again worth what they think it ought to be worth. Home prices, like rents, are "sticky downward."

At the same time, what the bill mandates is that those houses are (eventually) sold to people that are presently renters. So house prices will fall a little bit in order to become affordable to that top tier of renters. So you get a mild, protracted drop in house prices that moves people on the margins of homeownership into homeownership.

When I read this bill it immediately reminded me of this paper about what happened when the Dutch government banned investor purchases of homes in certain neighborhoods. In those neighborhoods, home prices dropped slightly and the homeownership rate increased. But who were the new homeowners? They were, of course, significantly wealthier and significantly whiter than the renters that used to live in those units. To become a homeowner requires a higher income than being a renter, and proportionally fewer immigrants in the Netherlands have that. So the investor ban, in effect, gentrified those neighborhoods.

This bill would certainly do the same thing.

So this is not good solution to the problem. Breaks my heart to see Bernie on the list of cosponsors. Does anyone know any Bernie staffers? Please suggest that he should hire a housing policy person, especially one with a growing newsletter, excellent value alignment, a can-do attitude and a winning smile (this is me, please hire me Bernie).

How to fight big financial landlords

Look, I'm going to level with you—these are the early days of my thinking on the subject. But this is my current working theory.

The best way to fight big finance in housing is likely to be through strong tenant protections. Good cause eviction, right to counsel, limits on fees, legal protection from serial evictions, and light-touch rent controls. Why? These make it much harder for institutional players to execute their most aggressive strategies.

If tenants are well protected by living standards laws, that leaves little room for cost-cutting by deferring maintenance.

If tenants are protected from no-fault eviction and lease non-renewal, it helps prevent one of the key strategies for rent-raising: evicting in order to re-list at a much higher rent. Since large institutions are generally lawyered up, right to counsel is necessary in order for this legal right to be more than a formality.

Rent control has to be designed carefully, but is a necessary piece of the puzzle if we want to prevent "economic evictions"—rapidly hiking rents on an existing tenant to get them to move out, without going through the legal eviction process. New York's Good Cause Eviction law includes a 5%+CPI or 10% per year limit on rent increases, which strikes me as about right. This can keep pace with overhead and construction costs (pop quiz: how much do you think is typical monthly operating expenses for a two-bed in NYC? Answer on the bottom of your cereal box*). Vacancy decontrol not needed—re-listings should be subject to the same limits if there hasn't been a substantial remodel. This is vastly preferable to a more aggressive rent control with vacancy decontrol, since vacancy decontrol creates a huge incentive to evict, which landlords take advantage of.

Using tenant protections can prevent institutional landlords from pursuing "strategic, hands-on management" tactics for price-gouging. By keeping rent control light-touch, it avoids disincentivizing new development, many kinds of which are sorely needed in the US. This is because it minimizes the macro risk faced by property developers, who may legitimately worry about the possibility that inflation could outstrip their ability to increase rents—this is especially relevant to those who want to build housing affordably, who are likely to have pretty thin margins.

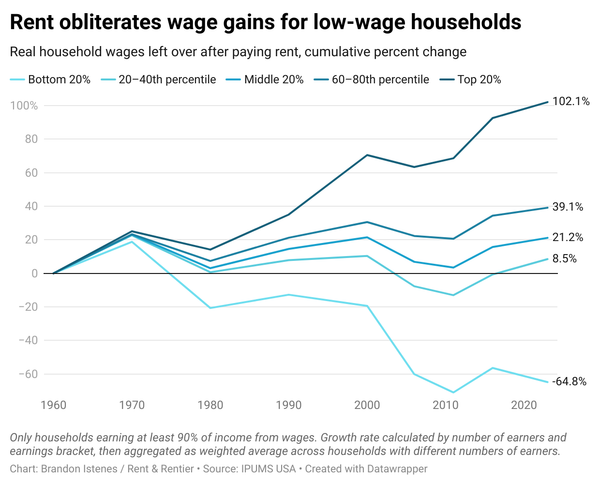

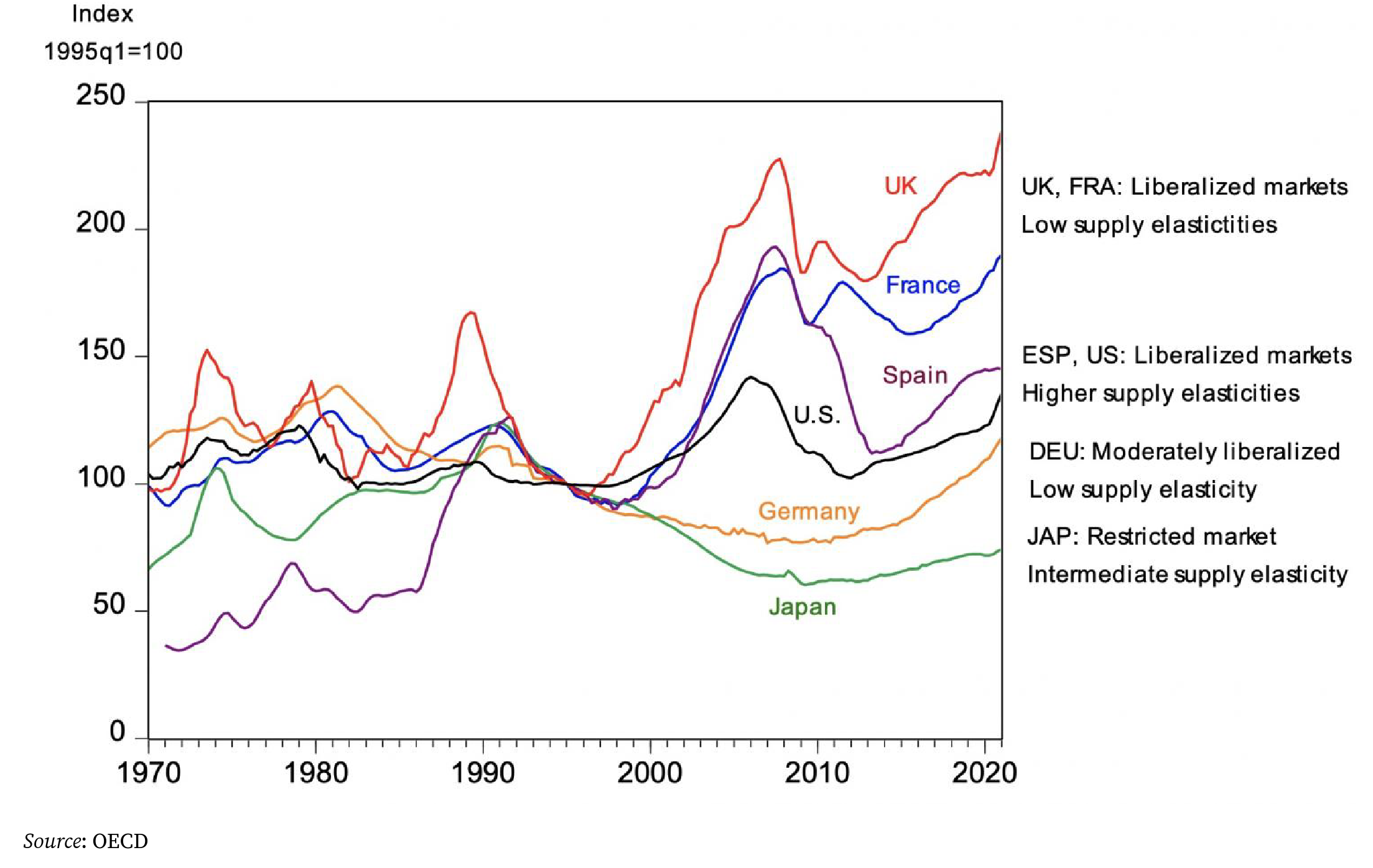

I suspect that these policies could put a damper on speculative activity in rental markets generally. There is some circumstantial evidence from the UK that the elimination of tenant protections lined up with increases in rents both in the late 1980s and after 1997. Landlords willing to put up with strong tenant protections are likely to be pursuing moderate, steady profits over the long term—very different from the private equity "gut it for profit and run" model. And I've been thinking about this graph from CEPR a lot, especially Germany and Japan:

The other great thing about these kinds of tenant protections, Good Cause etc., is that they largely do what they say on the tin. Perverse second-order effects are generally few and mild in comparison with the dramatic improvement to tenant stability and quality of life (this is only true of rent control if the policy is well-designed and light-touch). And I suspect that the effects on market stability might be very positive.

The other way to fight big finance in housing

The other thing to note is that big finance gets into housing when it sees large profit opportunities. These opportunities were especially present in the post-'08 GFC recovery and the post-pandemic recovery. Finance waits until it sees an opportunity and then springs on it.

These opportunities are created by economic instability and by supply shortages.** By smoothing out the housing investment cycle, we can prevent the kind of market craziness that produces big opportunities for big finance.

A little prognostication

Permit me to go out on a limb: I think we are going to see mid-size and large institutional landlords of the traditional sort (the kind not included in "hedge funds" in the Merkley bill) get more aggressive with their pricing strategy. Some of the strategies pursued by financial landlords only work with a short investment horizon, like avoiding maintenance. Traditional institutional landlords, who generally hold for the long term, are not interested in letting the property go to hell. But there's no reason to believe they wouldn't run experiments with "test units," for example. Even if YieldStar is banned, large institutional landlords are getting more clever, and that's bad for renters.

It is thus a matter of sound political economy that the economically ideal landlord is basically Ms. Hudson from Sherlock Holmes—kindly, a bit bumbling, and does not know how to use the internet.

Of course, we also need people that are going to build nice apartment buildings, and that's a little hard to square.

But why fetishize SFH and homeownership in the first place?

Prioritizing homeownership of single-family homes seems like a very weird priority for the left to take up. The historical analogies are not particularly flattering: Thatcher and Franco.

Thatcher initiated the sell-off of the UK's Council House stock through "Right to Buy," partly to dismantle the public sector and partly to increase homeownership, which Tories saw as a virtue in itself. A "property-owning democracy" was seen as supporting a conservative social order.

In Francoist Spain, meanwhile, there wasn't really a public housing stock to sell off, but homeownership was seen as a priority for roughly the same reasons for the fascists as for the Tories. The dictatorship achieved this in a variety of ways, including mass public construction of cheap houses for sale with public financing, and the use of aggressive rent control to effectively destroy the rental market. Spain now has one of the highest rates of homeownership in Europe.

I think examples like Germany, where 53% of the population rents, show that a low homeownership rate puts the majority on the side of renters in politics. Just about everywhere in the world, renters are generally poorer, more diverse, and more marginalized than homeowners. In the US, politicians can be successful without appealing to tenants, because tenants are in the minority. In Germany, a tenant-majority country, tenant protections are first-class political concerns. It's similar to how the retirement programs that are the best for poor people are actually the least targeted ones—"universal" or "comprehensive" social insurance—the ones that work well for a broad constituency of voters.

Finally, the US's addiction to single-family homes is not environmentally sustainable. They are the basic unit of sprawl. They require car-dependent lifestyles and displace a huge amount of green space per family. And they are at the center of the shrine of zoning. Zoning prioritizes SFH in order to keep the poor out and subsidize SFH living for the wealthy.

That vision thing

Getting these properties out of the hands of large financial institutions would be nice, but what if we could get them out of the for-profit housing sector altogether? I'm not sure about the prospects for a US edition of Deutsche und Wohnen Enteignen, but there are useful next steps.

Cities and states with high shares of institutional SFR ownership should aim to pass Community Opportunity to Purchase (COPA) rules for large institutional landlords, revolving loan funds, and stronger tenant protections. The tenant protections encourage financial landlord divestment (and protect tenants), COPA facilitates the acquisition by non-profit-seeking entities, and the revolving loan funds provide the financing for the acquisition.

On top of that, they should work to set up public housing authorities that can access capital (e.g. from the revolving loan fund) to acquire housing. They should have the latitude to operate rentals at market rate. Whether a non-profit or public institution makes the acquisition, the tenants get to stay, and their rent stops going up. Allowing rent to stay at or near current levels means the buyer doesn't have to find a huge pile of money to buy the houses elsewhere (e.g. taxes). As the house gets paid off, rents don't have to rise at all, and eventually can be rented at operating cost. See the footnote immediately below on operating costs.

*Typical NYC two-bed operating expenses are around $1000 monthly, not including taxes.**Very clarifying quote from the Preqin Alternatives 2025 report (Preqin is an arm of Blackrock): "In the short term, we’re still working through elevated levels of deliveries in some sectors, for example the US apartment market. But very little construction has started over the last two years, which means this short-term headwind is already beginning to heal itself. As a result of the fall-off in new starts, construction levels are already down to prepandemic levels, so the worst of the supply headwinds are behind us. In the medium term, there’s an opportunity for investors to capitalize on improving fundamentals as a result of decreasing new supply amid rebounding demand. Meanwhile, reset values and the opportunity for price appreciation further sweetens the pot." In other words, financial capitalists would much rather have a supply shortage than more development.